A cure for the housing crisis

Next time you’re walking around Philly (or any US city for that matter) take note of all the vacant lots. Notice how many derelict buildings stand on crowded streets. Pay attention to all your neighbors experiencing homelessness.

Why is it that houses are so expensive that homeownership is a pipedream for most Americans, and yet at the same time prime real estate can sit vacant? It’s not because landlords have suddenly lost interest in making money. It’s because our tax system incentivizes waste.

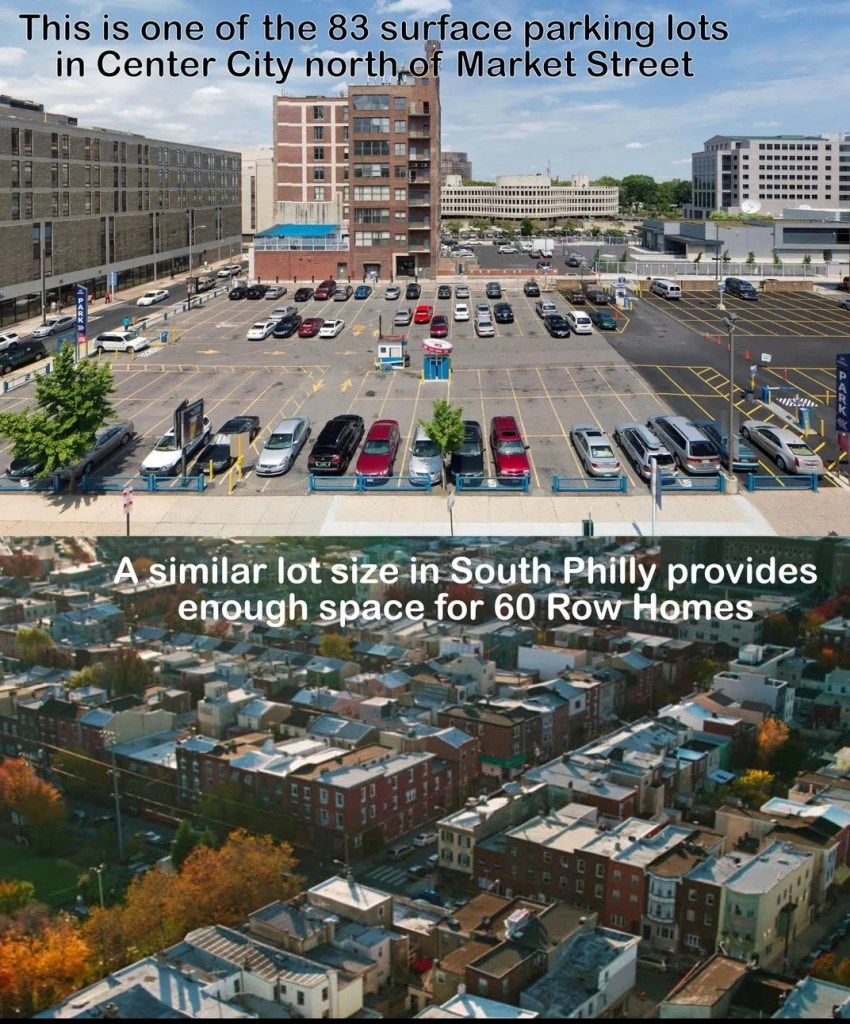

Property taxes are determined mostly based on the value of what’s built on top of someone’s land. If a parcel of land has a multi-million dollar apartment complex, the owner will have a higher property tax than the owner of a parking lot on the same-sized parcel of land. If the parking lot owner builds a house on their land, their property taxes will go up. This system disincentivizes development.

An alternative gaining popularity involves a Land Value Tax (LVT). This would assess taxes based on the value of the land itself, rather than the property built on top of that land. A 1-acre vacant lot in Center City would be more valuable and therefore taxed at a higher rate than a 1-acre vacant lot in a rural community. Under a LVT system, the landowners taxes stay mostly the same whether they leave it vacant or build housing. While a vacant property gets taxed while not generating any revenue, an apartment complex should generate more than enough revenue to cover essentially the same tax. LVT encourages land owners to put their land to productive use or sell it to someone who will.

Philadelphia already recognizes that property taxes disincentivize development. For years, the city offered 10-year tax abatements on new constructions and renovations. While this did stimulate growth, it sacrificed much needed revenue for America’s poorest big city. A 2018 study found that buildings with abatements would otherwise have contributed $111 million to the city. LVT would avoid the disincentives of property taxes without hampering the city’s budget.

The urbanist PAC, 5th Sq, got it right when commenting on the Mayor Parker’s FY26 budget saying,

“The path to preserving the positive effects of the abatement while avoiding the negative effects, is to cut the property tax rate on improvements, and raise the rate on land, for all properties in the city. In contrast to improvements, land is in fixed supply, so a tax on land can not discourage its production. At the same time, the value of land is generally created not by the landowner, but the public and private investments around the land. Thus, the value of land arguably ought to be returned to the public through a tax.”

The status quo cannot continue. According to the city, there are approximately 40,000 vacant properties in Philadelphia. Nevertheless, 5,200 Philadelphians were estimated to be experiencing homelessness in 2024. Even the housed are struggling. The median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Philly is $1,500, but the city’s median income is $57,000. “Cost-burdened” is a term housing economists use to describe people who have to spend more than 30% of their income on housing and utilities. Over half of Philly is cost-burdened.

To change that, workers either need to start making more, or housing costs need to start falling. You’d need to work 90 hours a week on Pennsylvania’s pathetically low minimum wage of $7.25/hour to afford a modest two-bedroom apartment in Philly at the fair market rate. With Republicans controlling the PA senate, workers shouldn’t expect relief any time soon. We can’t expect the federal government to help either. For example, Trump recently moved to terminate a $1 billion program aimed at preserving affordable housing, a decision that could disrupt efforts to maintain tens of thousands of units for low-income Americans. Therefore, Philly needs to address the other half of the equation by lowering the cost of housing. As we’ve seen elsewhere, Land Value Tax can do this.

Our neighbors in Allentown, PA adopted LVT back in 1996 leading to a boom in construction, market investment, and capital improvements in the city budget. Even a Republican senator, Pat Toomey, had to admit, “The number of building permits in Allentown has increased by 32 percent from before we had a land tax.” In 1982, LVT saved our capital, Harrisburg, from bankruptcy. After instituting a tax rate on land that was four times the rate on buildings, the number of vacant buildings declined from over 4,200 in 1982 to under 500 by 2001, and the number of businesses on the tax roll grew from 1,908 to nearly 9,000. Case studies can also be found abroad, with success stories in places as diverse as Taiwan, Mexico, and Denmark.

No policy comes without tradeoffs. While renters and hopeful homebuyers will benefit, such a significant disruption in the tax system will impact current homeowners’ budgets. In cities where LVT has been successfully implemented, it has sometimes been repealed due to issues with land value and property reassessments. It is also important to note that municipalities rarely adopt a pure LVT. Rather, most employ a split-rate system involving a mix of taxes on land and property improvements, typically at a 5:1 ratio. The nuances of proper implementation and supplemental policy to alleviate any potential displacements are worthy of discussion, and I encourage you to share your ideas in the comments!

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution will help the Philthy Liberal grow! Any amount is greatly appreciated!

A monthly contribution of any amount will help keep this independent blog running. Thanks in advance!

An annual contribution of any amount will help keep this independent blog running. Thanks in advance!

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

Leave a comment